Context: While some major media companies prefer to resolve any AI copyright questions amicably through license agreements, litigation over how AI systems use copyright material is rampant (April 30, 2024 ai fray article). The highest-profile case of this kind is arguably New York Times v. Microsoft & OpenAI (Southern District of New York, case no. 1:23-cv-11195). The parties are in the process of working out a protective order (a court order to regulate the handling of confidential business information exchanged in discovery). On Wednesday (May 1, 2024), the New York Times’ lawyers sent a letter to Judge Sidney Stein, blaming Microsoft and OpenAI for the parties’ inability to agree on the text of a protective order.

What’s new: Yesterday (May 3, 2024), Microsoft’s and OpenAI’s lawyers responded and explained why they believe certain modifications to the NYT’s proposed protective order are necessary. The second of three respects in which the defendants’ proposal differs from the NYT’s raises the issue that the New York Times, which is reporting extensively on its own case (the letter respects the NYT’s right to do so), might use some lawyers’ access to confidential documents in editorial decision-making, even if just inadvertently. Put differently, the defendants want a Chinese Wall between the NYT’s in-house lawyers working on this litigation and lawyers involved with editorial decisions, such as through “prepublication review of reporting about [Microsoft and OpenAI].”

Direct impact: It could be that the parties still reach an agreement that obviated a judicial decision. Otherwise Judge Stein will have to make a determination on the terms of the protective order. There are no accusations here of the NYT having done anything improper so far, but one must wonder why the NYT’s lawyers have not previously agreed to a wording that simply ensures confidential information cannot influence the NYT’s reporting on this copyright case or on Microsoft and OpenAI in other contexts.

Wider ramifications: Publishing companies owning influential media are always tempted to leverage their clout in connection with their own commercial interests and legal disputes. There are reputational and litigation-related risks involved. It is, however, obvious that some cases are so important that not reporting on them is not an option even if the reporters’ employer is party to the proceedings.

In their May 1, 2024 letter (PDF), the NYT’s lawyers from litigation powerhouse Susman Godfrey stated they had “made every effort to negotiate [protective orders] with Defendants [Microsoft and OpenAI]” and blamed it on their adversaries that no solution has been found after a couple of months.

Yesterday’s response was submitted by Microsoft’s lawyers from Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe (about a high-profile fair use case they were previously involved in, see thisJanuary 24, 2024 ai fray article) and also signed by OpenAI’s lawyers. The NYT had chosen to make Microsoft the first-named defendant, though what is at issue is OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

The defendants’ attorneys say in their latter that the parties are not far apart, but a few issues have not been resolved yet, which is why they ask Judge Stein to adopt their proposed proective order, not the NYT’s. Here’s the defendants’ letter along with various exhibits:

The first and third changes Microsoft and OpenAI would like to make to the proposed protective order are just procedural: they relate to a clawback provision and a process for challenging confidentiality designations.

The second part, however, is not what one finds in many litigations:

Defendants propose adding an “Editorial Decision-Making” category to the otherwise agreed-upon bar against disclosure of “HIGHLY CONFIDENTIAL – ATTORNEYS’ EYES ONLY” material to certain inhouse counsel of the Receiving Party. Ex. A at ¶ 15(b).

This is about the extent to which inhouse counsel can be granted access to documents designated as “HIGHLY CONFIDENTIAL – ATTORNEYS’ EYES ONLY.” Inhouse counsel is also bound by professional rules, but at the same time is less independent than outside counsel and may often become involved in internal meetings or written communications.

A very common approach in commercial litigation is that only some of a company’s in-house lawyers may get access to such documents at all, and only if reasonably necessary on a case-by-case basis. In terms of what inhouse lawyers may be members of that confidentiality club at all, it is routinely agreed upon that lawyers involved in competitive decision-making are ineligible. Put differently, the idea is that inhouse lawyers should get access to such highly sensitive material only for the purpose of enabling a legal department to manage the litigation, but not for other purposes that could have commercial implications.

This provision is crucial because Plaintiff continues to report extensively on this litigation. Defendants recognize that The New York Times has a right to report the news.

Those two sentences are a way of diplomatically suggesting between the lines that the NYT is leveraging the power of its influential newspaper to influence the litigation. That is not waht the letter says literally, but the adverb “extensively” (and to a lesser degree also the verb “continues”) comes with the connotation that the NYT is reporting more on this AI copyright case than the average newspaper would do in connection with even a high-stakes (given that the NYT is suing for billions of dollars) legal dispute.

Still, Microsoft and OpenAI do not want to come across as enemies of the freedom of press. So they restate the obvious: the NYT has the right to report on this.

But it would be inappropriate for The New York Times’ inhouse attorneys conducting, for example, prepublication review of reporting about Defendants to have access to Defendants’ highly confidential information. There is too great a risk that Defendants’ highly confidential information may be improperly used, even if inadvertently. The Court should not allow Plaintiff to use the discovery process to transmit confidential information to its editorial staff.

Here it’s important to consider the stage of litigation: nothing like this has happened. There is no wrongdoing that Microsoft and OpenAI are complaining of, not even between the lines. And it’s not that they want this to be seen as expressing distrust of the NYT’s lawyers’ integrity. They just want to be comfortable that those NYT in-house lawyers who do get access to highly sensitive material from Microsoft and OpenAI will not in any way have that information in mind when performing other functions, such as reviewing NYT articles on the litigation before they go live.

Given the aforementioned high stakes, it is fairly possible that the NYT’s lawyers want to see articles on their AI copyright case before they go live, as the content of those articles could somehow be held against them. The concern here is not a conflict of interest in terms of how those lawyers might influence the reporting (though the judge will obviously have that in mind when reading any NYT articles on the company’s own case). It’s that their could be articles about this copyright case, or also just generally about Microsoft and OpenAI, and someone who saw a highly confidential document may somehow suggest edits (such as striking, adding or rewording passages) to NYT articles before they go live.

As indicated in the summary further above, the only suspicious thing here is that the NYT as not readily accepted such a rule. If they don’t intend to do any of that, why is this an issue at all?

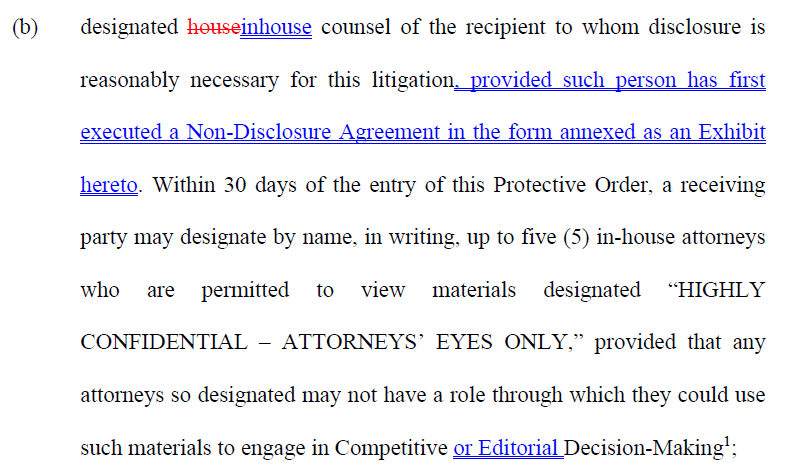

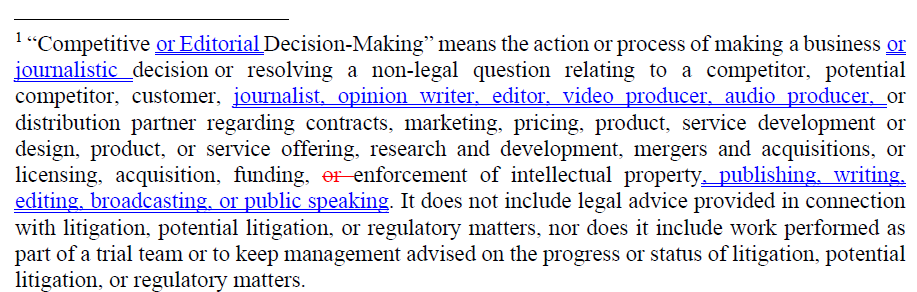

In the end, it’s about minor clarifications. Here’s the redlined version of the relevant passage, followed by the redlined version of the related footnote:

The blue underlined words are the ones Microsoft and OpenAI would like to add. There should be no dispute about that in the first place unless the NYT absolutely wants the same in-house lawyers who manage the litigation to review (and otherwise influence) the NYT’s reporting on the case and on the two defendants.